As part of our mission to support, celebrate, and promote literary magazines and presses, we showcase in this series short essays about the many publishers that have contributed to the collective story of independent publishing in our country.

“We are by far the oldest black publication in the world,” wrote Benjamin L. Hooks in his introduction to the December 1985 issue of The Crisis, “with a circulation of over 300,000, making us the fourth largest black oriented magazine in the nation.” 1985 was The Crisis’s 75th year of continuous publication.

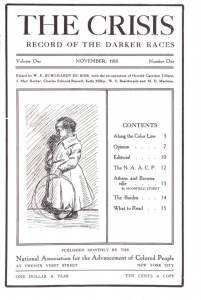

The official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), The Crisis was founded in 1910 and edited until 1934 by W. E. B. Du Bois. In his note accompanying the inaugural issue, Du Bois wrote, “The object of this publication is to set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested to-day toward colored people. It takes its name from the fact that the editors believe that this is a critical time in the history of the advancement of men.”

In that same issue, Du Bois went on to outline The Crisis’s mission: it would be both a newspaper, recording “important happenings and movements in the world which bear on the great problem of inter-racial relations,” and “a review of opinion and literature, recording briefly books, articles and important expressions of opinion in the white and colored press on the race problem.” It would also publish “a few short articles” and an editorial page standing “for the rights of men, irrespective of color or race.”

The magazine, with its mix of literature and both sobering and celebratory news, was a success. Circulation approached 16,000 in January 1912; by April of that same year it was at 20,000; by 1919 The Crisis was reaching 100,000 readers every month. And as it grew, it featured writers who themselves were becoming vital figures in American literature, specifically in the Harlem Renaissance. Du Bois published poems, stories, and plays by Alice Dunbar Nelson, Leslie Pinckney Hill, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Lucian B. Watkins, and many other pivotal writers of the era.

Late in 1919, Du Bois handed literary editorship of the magazine over to Jessie Redmon Fauset, a frequent contributor who had published her first poem in The Crisis in April 1912. Langston Hughes would later cite Fauset as one of three editors “who midwifed the so-called New Negro literature into being. Kind and critical—but not too critical for the young,” he wrote, “they nursed us along until our books were born.”

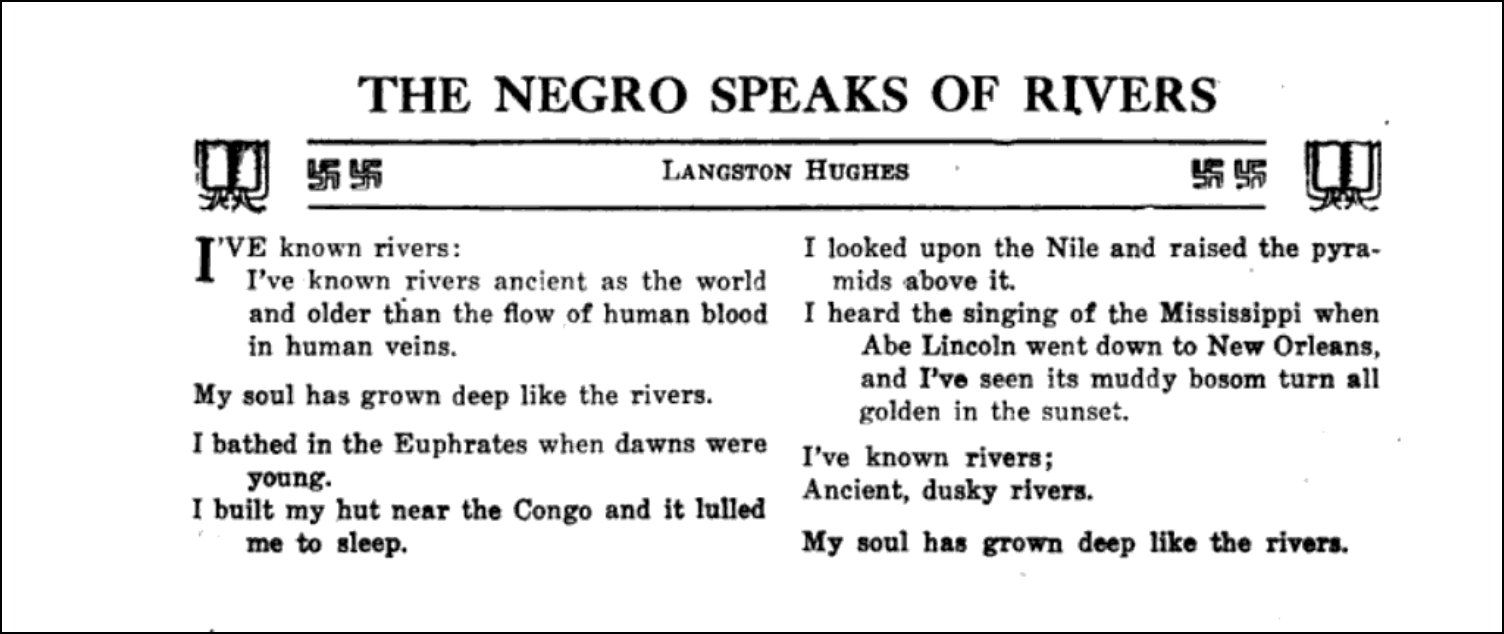

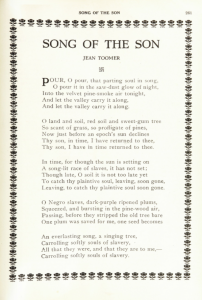

This is no exaggeration; Cheryl A. Wall told Morgan Jenkins in 2017, “The Harlem Renaissance as we know it would not have been possible without [Fauset’s] participation.” Thanks to Fauset, Hughes’s first published poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” appeared in the pages of The Crisis in June 1921, and his work shows up regularly in subsequent issues. Fauset also published Joseph Seamon Cotter, Effie Lee Newsome, Anne Spencer, and numerous other major voices from the Harlem Renaissance. Jean Toomer’s poem “Song of the Son” appeared in April 1922; Countee Cullen’s “If You Should Go” came two months later.

This is no exaggeration; Cheryl A. Wall told Morgan Jenkins in 2017, “The Harlem Renaissance as we know it would not have been possible without [Fauset’s] participation.” Thanks to Fauset, Hughes’s first published poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” appeared in the pages of The Crisis in June 1921, and his work shows up regularly in subsequent issues. Fauset also published Joseph Seamon Cotter, Effie Lee Newsome, Anne Spencer, and numerous other major voices from the Harlem Renaissance. Jean Toomer’s poem “Song of the Son” appeared in April 1922; Countee Cullen’s “If You Should Go” came two months later.

Many of these writers went on to be featured in The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke, another of the three editors Hughes mentioned. The third of these editors was Charles S. Johnson of Opportunity, a magazine that launched in 1923 and was one of several additional publications amplifying Black voices around this time. Others included Colored American Magazine, edited by Pauline E. Hopkins, which ran from 1900 to 1909; Negro World, a magazine in the 1920s and early 1930s founded by Marcus Garvey; The Book of American Negro Poetry, a 1922 anthology edited by James Weldon Johnson; and Caroling Dusk, a 1927 anthology edited by Countee Cullen.

The Crisis went on to publish members of the Harlem Writers Club in the 1950s, and it is still published as a quarterly magazine today. Although it now primarily prints articles and opinion pieces, rather than original literary pieces, it maintains strong ties to the literary community; for instance, Jabari Asim, author of Stop and Frisk: American Poems (Bloomsday, 2020), served as the magazine’s editor-in-chief from 2007 to 2017. The magazine is currently edited by award-winning journalist Lottie Joiner.