As part of our mission to support, celebrate, and promote the work of literary magazines and presses, we showcase in this series short essays about writers whose careers were supported by independent literary publishers.

In 1986, the poet Audre Lorde gave the keynote address, titled “Sisterhood and Survival,” at the Black Woman Writer and the Diaspora conference. To the gathered crowd, she said, “I am a black feminist lesbian poet, and I identify myself as such because if there is one other black feminist lesbian poet within the reach of my voice, I want her to know she is not alone.”

Lorde’s intention reached far beyond the one hypothetical poet she was speaking to in that 1986 crowd—her life’s work and legacy continue to influence poets today. As Mahogany L. Browne writes, “Her work instilled a hope, an expectation I didn’t realize was my birthright.” Cedar Sigo writes, “Lorde’s perceptions around race, sexuality, and class seemed to put me within reach of emotions I have kept buried for twenty years.” Cheryl Clarke writes, “She had the ability and privilege to be a visceral public presence. She used that privilege just as she used her voice to make blackness, feminism, lesbianism heard; and she used blackness, lesbianism, and feminism to make her voice heard.”

Lorde’s intention reached far beyond the one hypothetical poet she was speaking to in that 1986 crowd—her life’s work and legacy continue to influence poets today. As Mahogany L. Browne writes, “Her work instilled a hope, an expectation I didn’t realize was my birthright.” Cedar Sigo writes, “Lorde’s perceptions around race, sexuality, and class seemed to put me within reach of emotions I have kept buried for twenty years.” Cheryl Clarke writes, “She had the ability and privilege to be a visceral public presence. She used that privilege just as she used her voice to make blackness, feminism, lesbianism heard; and she used blackness, lesbianism, and feminism to make her voice heard.”

Lorde was born in New York City on February 18, 1934. She wrote poetry while attending Hunter High School, and she received a BA from Hunter College in 1959 and an MLS from Columbia University in 1961. In 1962, Langston Hughes included her poem “Pirouette” in his groundbreaking anthology New Negro Poets, USA (University of Indiana Press, 1962).

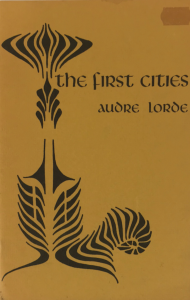

From the beginning, Lorde’s career was connected with, and her voice championed by, independent literary publishers. Her debut poetry collection, The First Cities (1968), was published by the New York–based Poets Press, which was founded by poet Diana di Prima and featured work by fellow literary luminaries Allen Ginsburg, Robert Creeley, Frank O’Hara, and A. B. Spellman. Lorde’s second book, Cables to Rage (1970), was published by Paul Breman in London before finding a home with Broadside Press, founded by poet Dudley Randall in Detroit, Michigan, in 1965. (Of this founding, Randall said, “I think the vigor and beauty of our Black poets should be better known and should have an outlet.”) Lorde published her next books, From a Land Where Other People Live (1973) and The New York Head Shop and Museum (1974), with Broadside Press as well.

From the beginning, Lorde’s career was connected with, and her voice championed by, independent literary publishers. Her debut poetry collection, The First Cities (1968), was published by the New York–based Poets Press, which was founded by poet Diana di Prima and featured work by fellow literary luminaries Allen Ginsburg, Robert Creeley, Frank O’Hara, and A. B. Spellman. Lorde’s second book, Cables to Rage (1970), was published by Paul Breman in London before finding a home with Broadside Press, founded by poet Dudley Randall in Detroit, Michigan, in 1965. (Of this founding, Randall said, “I think the vigor and beauty of our Black poets should be better known and should have an outlet.”) Lorde published her next books, From a Land Where Other People Live (1973) and The New York Head Shop and Museum (1974), with Broadside Press as well.

During this time, Lorde’s writing regularly appeared in literary magazines, including her poem “Black Mother Woman” in the Massachusetts Review (1972) and “Power” in The Iowa Review (1975). She was also an active figure in the literary community, serving over the years as a poetry editor of Chrysalis and Amazon Quarterly, a contributing editor of Black Scholar, and an editor of Pound magazine.

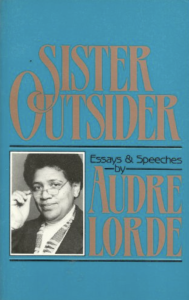

In 1976 Lorde’s poetry collection Coal came out with W. W. Norton, and though she continued to publish poetry with this major independent publisher—including The Black Unicorn (1978) and Undersong: Chosen Poems Old and New (1992)—she kept working with smaller feminist presses as well. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Lorde’s fiction and nonfiction appeared with Eidolon Editions, founded by di Prima in 1972; Spinsters Ink, founded by novelist Joan Drury in 1978; Firebrand Books, founded by Nancy Bereano in 1984; and The Crossing Press, founded by Elain Goldman Gill and John Gill and publishing, according to a New York Times article about successful small presses of the 1980s, “feminist fiction and books for the homosexual community.” It was The Crossing Press that published Lorde’s best-known work, the collection of essays and speeches Sister Outsider, in 1984.

In 1980, Lorde gathered with Black feminist writer Barbara Smith and several other women to found their own independent literary publisher, Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. Smith later wrote, “If any one had asked in 1980 whether books by women of color could sell or whether a press that published only work by and about women of color could survive, the logical answer would have been ‘no,’ especially if the person who answered was part of the commercial publishing establishment… Since the early 1970s, however, a small but devoted group of feminist activists, teachers, and writers, many of them Black women, have been working to make visible the writing, culture, and history of women of color. It was their work, not Madison Avenue’s, that laid the political and ideological groundwork for Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press and also for the current eighties renaissance of writing by Black and other women of color.”

From its founding through its closure soon after Lorde’s death in 1992, Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press played a vital role in championing women’s voices and connecting women writers of color—including poet Cheryl Clarke and activist Angela Y. Davis—with readers. In 1989, Smith reported that the average first printing for a Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press title was 5,000 copies. Its bestselling title, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, originally published by Persephone Press in 1981 and reprinted by Kitchen Table in 1983, had sold 47,500 copies by the time of Smith’s 1989 report; Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (1983) had sold 17,500.

In 1989, Lorde’s essay collection A Burst of Light (Firebrand Books, 1988), detailing her struggle with cancer, won a National Book Award. She died in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, on November 17, 1992. “Those messages she has left with us are explicit and empowering,” wrote the poet Jewelle Gomez in “Audre Lorde: Passing of a Sister Warrior,” published in Essence magazine in 1993. “We need only open one of her books for that light to shine.”