We spoke with Sarah Kortemeier, the Library Director of the University of Arizona Poetry Center and curator of the Little Magazines exhibit, in this spotlight.

What is the University of Arizona Poetry Center?

The University of Arizona Poetry Center, based in Tuscon, is a special-collections library and literary arts center dedicated to contemporary poetry. We have been collecting contemporary poetry and hosting visiting poets in our Reading and Lecture Series since the early 1960s. The Poetry Center started off with a few hundred volumes of poetry and two cottages donated to the University of Arizona by our founder, Ruth Walgreen Stephan. Since then, the collection has grown to more than 80,000 poetry books, broadsides, photographs of poets, and recordings, and it’s now housed in the award-winning Helen S. Schaefer Building on the north side of campus.

The University of Arizona Poetry Center, based in Tuscon, is a special-collections library and literary arts center dedicated to contemporary poetry. We have been collecting contemporary poetry and hosting visiting poets in our Reading and Lecture Series since the early 1960s. The Poetry Center started off with a few hundred volumes of poetry and two cottages donated to the University of Arizona by our founder, Ruth Walgreen Stephan. Since then, the collection has grown to more than 80,000 poetry books, broadsides, photographs of poets, and recordings, and it’s now housed in the award-winning Helen S. Schaefer Building on the north side of campus.

On the programming side, in addition to our long-running Reading and Lecture Series, the Poetry Center runs children’s art and writing workshops, community classes, writing residencies, and the state Poetry Out Loud competition for Arizona high school students. On the library side, the collection is open to the public Tuesdays through Saturdays during the academic year, and we display a rotating schedule of physical exhibitions showcasing collection items and work by visiting artists.

Our print collections are non-circulating, but folks outside Tucson can access some of our materials online: For example, all the historical recordings from our Reading and Lecture Series are available on Voca, our online audiovisual archive. We’ve recently started live-streaming almost all of our Reading and Lecture Series events, to include audiences who can’t be with us in person; live-streaming and other details for individual events can be found on our calendar. The Poetry Center’s Archivist and Outreach Librarian, Julie Swarstad Johnson, produces a podcast called Poetry Centered with assistance from Library Specialist Aria Pahari; the podcast offers samplings of Voca recordings selected by guest poet-curators. Our website includes an online gallery featuring photographs of poets taken by the Poetry Center’s first director, LaVerne Harrell Clark. Most recently, we’ve added an online exhibition platform, which we launched during the early COVID-19 pandemic to give users some access to our collections while our building was closed. Little Magazines is the latest exhibition in that series.

Can you tell us about the Little Magazines exhibit? What inspired the focus on independent literary journals?

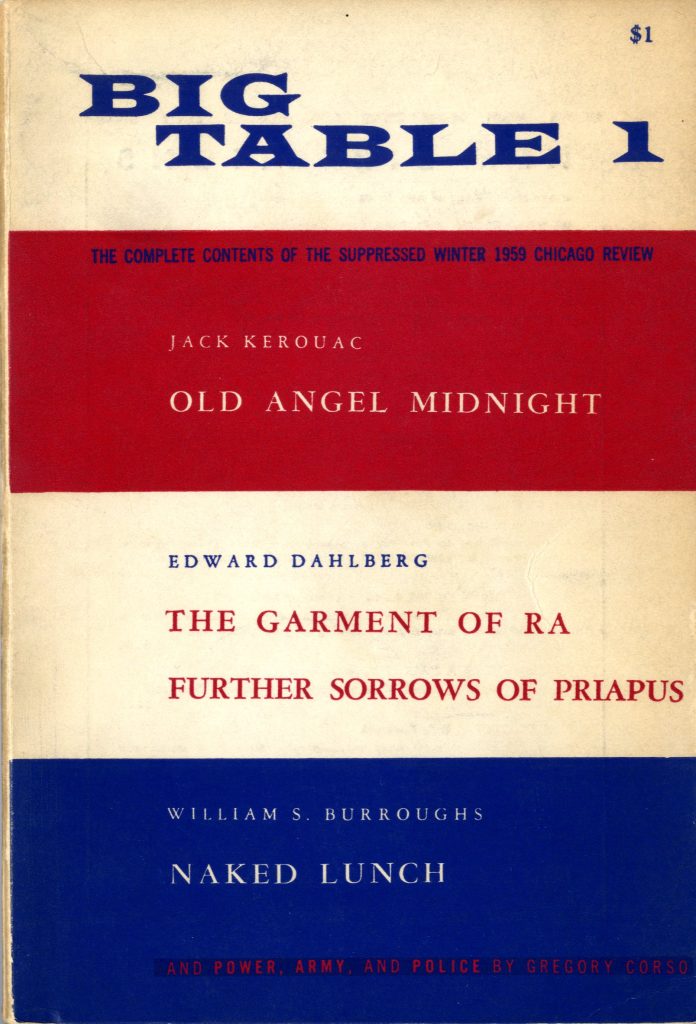

Little Magazines showcases a small sampling of the tens of thousands of back issues of literary periodicals we’ve accumulated over the past sixty years. As a special-collections library, we retain all our collection items in perpetuity; we don’t deaccession older issues of journals, because we view them as part of the history of contemporary poetry.

Little Magazines showcases a small sampling of the tens of thousands of back issues of literary periodicals we’ve accumulated over the past sixty years. As a special-collections library, we retain all our collection items in perpetuity; we don’t deaccession older issues of journals, because we view them as part of the history of contemporary poetry.

However, preserving all that history doesn’t do much good unless the public has access to it, and access to this collection is a bit tricky. Our back periodicals take up quite a lot of shelf space, which means we don’t have room for most of them in our public Reading Room. We have to shelve them instead in one of our closed-stack spaces, away from the public eye. While all these materials are available on request, you can only request materials when you know they exist! So the impetus for this exhibit came primarily from a desire to let the public see a bit more of what we have. We hope this sampling of journals whets folks’ curiosity; we’d love to see our periodicals become more widely read.

Why is it important to continue celebrating and reading “little magazines”?

Little magazines are such important signposts in the literary landscape. When I work with students in the library, I always tell them to consult our little magazines to read the newest poetry available—little magazines so often have that element of “newness” and experimentation, especially the indie, kitchen-table productions. Because we’ve got historical as well as current issues of these magazines, we can use them to look back, to trace the beginnings of movements and schools in American poetry in their pages. Most poets’ first publications come in little magazines; some poets’ only publications happen in little magazines. We need to read these journals to understand the breadth of contemporary poetry—books alone don’t tell the full story.

How did you decide which issues in the Poetry Center Library’s archives to feature?

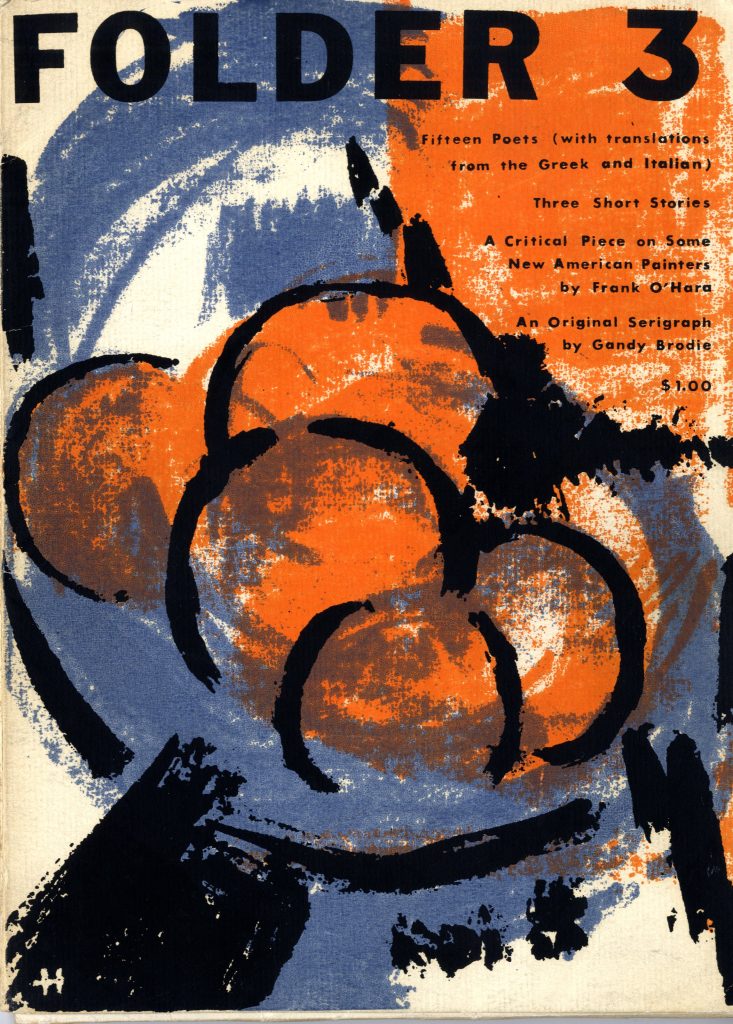

I was certainly spoiled for choice—and I had to leave so much out! The choices felt almost arbitrary. But, with that said, I tried to make choices that reflect the linguistic, geographic, and cultural diversity of our periodicals collection. We have a number of important journals from the midcentury mimeo tradition and the New York School alongside multilingual borderlands literary journals, for example. I also tried to feature journals that had lots of visual interest. The midcentury journal Folder is packed with so much gorgeous artwork that I couldn’t narrow my photographs down—I just threw up my hands and published all of them. Finally, I looked for opportunities to showcase journals that are held by no other library in North America, and that search led me to include Conquest, which published writing and art by community college students and incarcerated youth in southern Arizona in the 1980s.

I was certainly spoiled for choice—and I had to leave so much out! The choices felt almost arbitrary. But, with that said, I tried to make choices that reflect the linguistic, geographic, and cultural diversity of our periodicals collection. We have a number of important journals from the midcentury mimeo tradition and the New York School alongside multilingual borderlands literary journals, for example. I also tried to feature journals that had lots of visual interest. The midcentury journal Folder is packed with so much gorgeous artwork that I couldn’t narrow my photographs down—I just threw up my hands and published all of them. Finally, I looked for opportunities to showcase journals that are held by no other library in North America, and that search led me to include Conquest, which published writing and art by community college students and incarcerated youth in southern Arizona in the 1980s.

Some of these print issues are particularly fragile. Can you tell us more about the Poetry Center’s work preserving them?

Our historical print journals are in varying states of fragility or repair, depending on how they were produced and the journey they took to reach us. By shelving them in a closed-stack space, we can lengthen their usable lives in a number of ways. For one, our closed-stack spaces are kept completely dark unless staff are actively working there; this protects our print resources from irreversible light damage (fading, weakening of paper, etc.). For another, our closed-stack spaces have their own air handler, which allows us to control the temperature and relative humidity in those rooms more precisely than we’re able to do for the building as a whole. (Seasonal fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity exert stress on paper-based materials over the long term, so it’s important to maintain consistent environmental conditions in our storage spaces.) The most fragile periodicals are also shelved in archival enclosures—usually an envelope or box made of acid-free, lignin-free paper or cardboard. Enclosures protect items from shelf wear and create a microclimate for each individual book or journal issue: Inside the buffer of the enclosure, temperature and relative humidity are more stable than they are in the air outside the enclosure. We’re slowly working to place all of our rarer materials—not just the most fragile items—inside archival enclosures.

When patrons ask to see a particularly fragile journal issue, our staff assesses the item’s condition and advises the patron on best practices for handling. For most print journals, clean, dry hands and common-sense gentleness are all that’s required. (Despite the romantic and popular appeal of white gloves, their use is contraindicated for most of our materials, as cotton gloves desensitize the hands and make it easy to accidentally rip paper.)

What are some favorite poems, stories, or essays you came across while curating this exhibit?

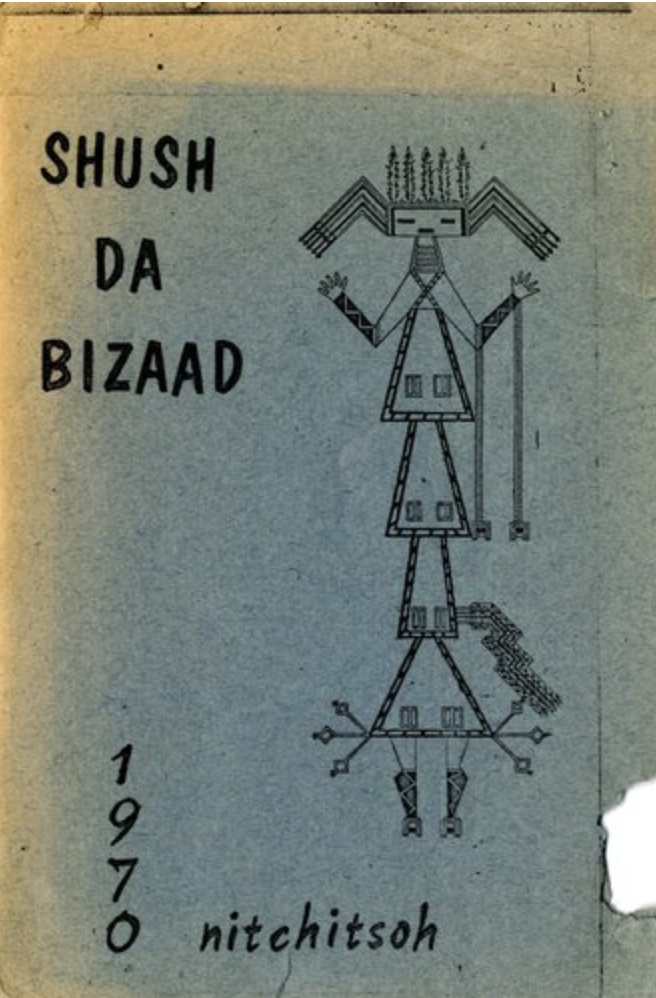

I was incredibly tickled to find an early Mark Doty poem in the University of Arizona journal Tongue. (Doty attended the University of Arizona in the early 1970s). Though he was a student at the time, traces of the mature poet are clearly visible: the religious symbolism, the economy of language, the arresting visual imagery. I was also delighted to find the work of Southwestern young people in Shush Da Bizaad (“Language of the Bears,” from Wingate High School in New Mexico) and Conquest (from Cochise Community College District and Arizona State Prison Complex–Douglas). The Southwestern border is such a rich cultural space, and these journals of youth writing speak powerfully to that richness.

I was incredibly tickled to find an early Mark Doty poem in the University of Arizona journal Tongue. (Doty attended the University of Arizona in the early 1970s). Though he was a student at the time, traces of the mature poet are clearly visible: the religious symbolism, the economy of language, the arresting visual imagery. I was also delighted to find the work of Southwestern young people in Shush Da Bizaad (“Language of the Bears,” from Wingate High School in New Mexico) and Conquest (from Cochise Community College District and Arizona State Prison Complex–Douglas). The Southwestern border is such a rich cultural space, and these journals of youth writing speak powerfully to that richness.